“In healthcare, everyone has two jobs: their job and the job of improving their job.”

Paul Batalden

Summary

Steps to completing a QI project.

- State the problem: succinctly summary what problem are we trying to solve and why.

- Understand the background:

- Understand the system by creating a flow chart. Share this with others and edit until you have a good depiction of how things work.

- Understand the theory by finding any literature on the topic. It may come from outside of healthcare.

- Understand the people and their motivations by interview to people who do the job. What drives them to make the decisions they make.

- Understand variation by plotting data over time. Then try to explain why outliers happen.

- Answer three fundamental questions:

- AIM: State what you are trying to accomplish including how good, by when and by whom.

- METRICS: Define metrics for success (and failure).

- CHANGE: Come up with a plan to meet those metrics.

- Test small-scale prototype solutions and iterate based on your successes or failures (using multiple PDSA cycles)

- PLAN: Craft a plan to implement the change described above. Design an experiment to test your change.

- DO: Do the experiment and document observations. Collect data based on your metrics.

- STUDY: Analyze the data from the experiment. Was it a success?

- ACT: Did we achieve our goal? Do we need to change our AIM or CHANGE or just refine the plan?

- Start the next PDSA cycle based on what you learned.

- Present your findings.

Introduction

Quality Improvement is the business of making healthcare better. The processes are borrowed from airline and industry safety initiatives such as those that drove Toyota to become a world leader in making cars. Knowing a little about the methods can help you fix problems you’ll later encounter.

The ACGME expects you to be able to reach Level 4 before graduation. Participation in a departmental QI project should get you to level 3 or 4.

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 Graduation Requirement | Level 5 Aspirational |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demonstrates knowledge of basic quality improvement methodologies and metrics | Describes local quality improvement initiatives (e.g., emergency department throughput, testing turnaround times) | Participates in local quality improvement initiatives | Demonstrates the skills required for identifying, developing, implementing, and analyzing a quality improvement project | Creates, implements, and assesses quality improvement initiatives at the institutional or community level |

How do we define better?

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), an independent, not-for-profit organization helping to lead improvement in healthcare around the world, defines quality by their triple aim for healthcare:

- to better care

- to improve the health of populations

- at a lower cost.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) defines “better care” over six areas (that spell STEEEP, note the extra “E”).

- SAFE: Safe care avoids injuries to patients from the care that is intended to help them by reducing hazards and risks.

- TIMELY: Timely care reduces waits and harmful delays for patients and providers.

- EFFECTIVE: Effective care provides the appropriate level of services based on scientific knowledge, matching science to care delivered.

- EFFICIENT: Efficient care eliminates waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy when delivering care with the goal of reducing cost.

- EQUITABLE: Equitable care doesn’t vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as race, socioeconomic status, etc.

- PATIENT-CENTERED: Patient-centered care is respectful of and responsive to the needs of individual patients allowing patients to be involved in the decisions that affect them.

Our healthcare system falls short in each of these areas time-and-time again. You can likely cite numerous examples for each category. However, by empowering each of us to make improvements, together we can work toward a system that provides better care for patients.

First Understand the Problem

“A problem well-stated is half solved.”

Charles Kettering (Head of Research at GM)

A well-worded problem-statement serves multiple purposes. It clarifies the goal to those who may be convinced to participate, justifies the effort expended, and communicates the importance of your efforts to others.

Before jumping to solutions, develop a well rounded familiarity with the problem. Systems problems can be understood in four ways:

- Understand the system: List all the steps in processes, where decisions are made and what happens next. Be sure that everyone understands the process the same way. The most common way to do this is through a flow diagram.

- Understand the theory: Search the literature to see if someone else has solved the same problem or if there are theories that may inform your solutions. Sometimes you may have to go to other industries. For example, in analyzing wait times in the Emergency Department, we may want to look at how Disney addresses waits for their attractions.

- Understand the people: Talk to the people who work in the system. Share your understanding of the system (flow diagram) and theory to see if it matches with their experience. They can tell you where the problem spots are.

- Understand variation: When trying to improve a particular outcome metric, plot it over time to identify where we performed well and where we didn’t. Use those outliers to learn what improves performance and what causes problems.

Understand the system

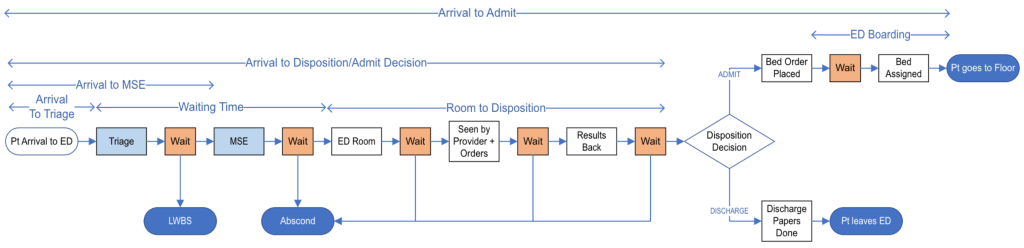

The most common way to appreciate how the different pieces of a system fit together is by drawing a flow map. For example, shown below is a flow map of the patient journey through an Emergency Department.

Share this map with others and match it to their experience. Make corrections based on their input until you have a good approximation of what really happens. Then share it with your team so everyone can work from the same mental model.

There are several programs to help create flow charts easily. You can make these using pen-and-paper, shuffling Post-It! notes around a wall, in PowerPoint, lucidchart.com, or draw.io. The video below shows how to build a similar flowchart in Microsoft Visio. We have access to this via our institutional Microsoft subscription. Just follow the instructions in the video.

Understand the theory

Next go to the literature and search for any solutions to the problem that may already exist. Start in the healthcare space, but expand to other industries if you don’t find anything. When looking for ideas on how to improve waits in the Emergency Department, you may look to queuing theory or lean manufacturing.

Understand the people

Next go to where the work is done and talk to people. Understand how they work in the system. Ask providers what is their understanding of what needs to get done, what motivations drive them (positive and negative) and what barriers prevent them from completing their work.

Understand the variation

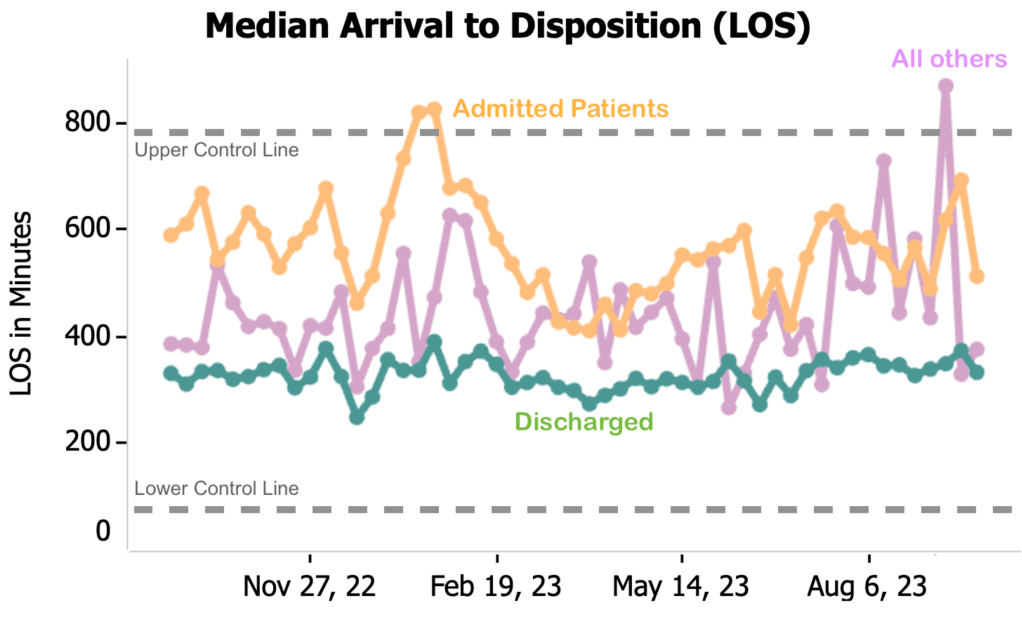

Finally, if there is a metric you’re trying to improve plot this against time on a run-control chart. You may see patterns emerge or identify outliers.

The chart below plots arrival-to-disposition (or length of stay) for three different patient populations: admitted patients, discharged patients and all others (eg, transfers).

The two dotted lines are the upper and lower control lines. These are usually set at one or two standard deviations above and below the mean. Points that fall outside these control lines are outliers. In the chart above, we see that the LOS for admitted patients raised significantly in December 2022 to January 2023. Explore what explains that deviation: this may identify an area to fix.

Watch the video below to learn how to easily make a dynamic run-control chart in Excel.

Exploring these four areas (the system, the theory, the people and the variation) helps you understand the problem more deeply and potentially unearth possible areas to direct your efforts when looking for solutions.

The Model For Improvement

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has developed a systematic and practical approach known as the Model for Improvement to drive change in healthcare. This framework empowers teams by providing a standardized approach to defining problems, designing potential solutions and testing the change.

Three Fundamental Questions

Aim Statements

The first step in the IHI Model for Improvement is to clearly define the aim of the project. The aim sets the direction for improvement efforts and articulates what is expected to be achieved. A well-crafted aim is specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). It provides a focus for the team and aligns everyone towards a common goal. It should clearly state “how good,” “by when” and “for whom?” Here are some examples:

- Reduce the 30-day hospital readmission rate for patients with heart failure from the current rate of 20% to 15% by implementing a comprehensive discharge planning program over the next six months.

- Decrease the average length of stay for non-critical patients in the emergency department from 4 hours to 3 hours within the next quarter by implementing process improvements in patient triage, diagnostics, and treatment.

- Increase overall patient satisfaction scores for the Emergency Department from the current average of 75% to 85% within the next four months by implementing customer service training for staff.

Metrics

Once the aim is established, the next step involves identifying and defining the measures that will be used to assess progress. Measurement is critical for understanding whether changes are leading to improvement. Teams should select meaningful and relevant measures that align with the aim of the project. These measures provide a quantitative basis for tracking and evaluating the impact of interventions.

These should be defined ahead of time so the QI team can track progress and adjust course as needed. There are several different types of metrics. The three critical ones are:

- Outcome Measures: assess the impact of the improvement effort on the overall aim of the project.

- Example: In a project aimed at reducing hospital readmissions, the outcome measure could be the percentage change in the 30-day readmission rate for a specific patient population.

- Process Measures: focus on the specific steps or activities undertaken to achieve the desired outcome. Monitoring these measures helps ensure that the intended changes are being implemented as planned.

- Example: In a project aiming to improve medication administration safety, a process measure could be the percentage of medication doses scanned using barcode technology.

- Balancing Measures: assess whether improvements in one aspect of the system have unintended negative consequences in another. These measures ensure a holistic view of the impact of changes.

- Example: In a project to reduce waiting times in the emergency department, a balancing measure might include monitoring the impact on the workload and stress levels of healthcare staff.

Additional metrics can be monitored, but for this project we won’t be addressing these.

- Structural Measures: assess the organizational and environmental factors that support or hinder the improvement effort. These measures provide insights into the readiness of the system for change.

- Example: In a project focused on enhancing team communication in a healthcare unit, a structural measure could involve assessing the availability and accessibility of communication tools.

- Patient and Family Experience Measures: capture the perspectives of those receiving care. Understanding their experiences is essential for patient-centered improvement efforts.

- Example: In a project to improve outpatient clinic services, patient experience measures may include satisfaction scores related to communication, appointment scheduling, and overall care quality.

- Utilization Measures: track the use of resources, services, or interventions. These measures help evaluate whether changes are leading to appropriate and efficient utilization of resources.

- Example: In a chronic disease management project, a utilization measure could be the frequency of follow-up appointments attended by diabetic patients.

- Financial Measures: assess the economic impact of the improvement effort. These measures are particularly relevant for healthcare organizations seeking to optimize resource allocation.

- Example: In a project aiming to reduce surgical site infections, financial measures may include the cost savings associated with a decrease in the number of infection-related complications.

- Safety Measures: focus on monitoring and improving the safety of care delivery. These measures are critical for preventing harm to patients and ensuring a culture of safety.

- Example: In a patient falls reduction project, safety measures could include tracking the number of falls with injury and assessing the effectiveness of implemented safety protocols.

Changes

The heart of the IHI Model for Improvement lies in making changes to the existing processes. Teams brainstorm and implement changes based on theories about what will lead to improvement. These changes are carried out during PDSA cycles.

Each potential solution will be specific to the task at hand, but you can use these as a starting point:

- eliminate waste (remove things that aren’t used, the flowchart workflow is very helpful to identify these)

- improves workflows (find and remove bottlenecks)

- optimize resources (match resources to predicted demand)

- enhance the provider-patient relationship, focusing on outcomes to the patient

- change the work environment (make it a better place to work)

- manage time (reduce start up or set up time)

- manage variation (standardization, creating a formal process)

- design systems to prevent errors (eg, use of reminders)

- focus on the design of products and services (eg, offer service any place)

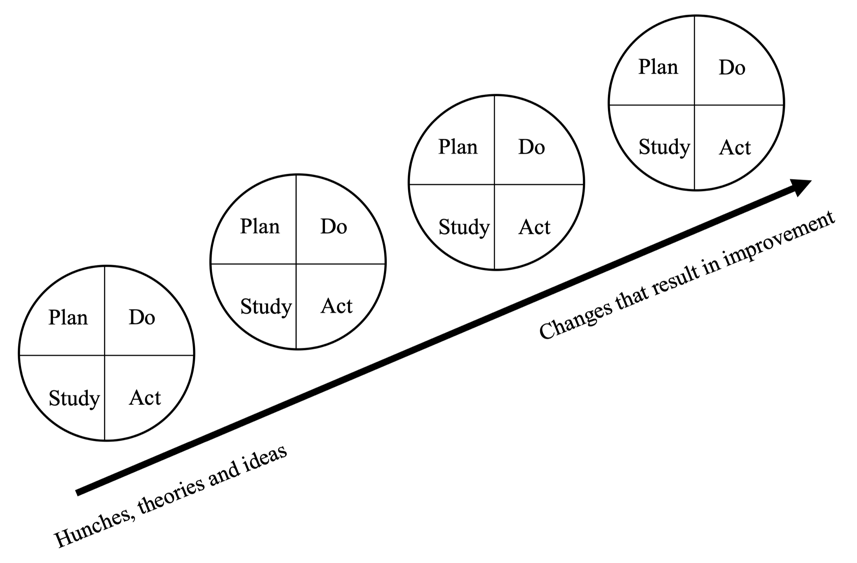

Plan-Do-Study-Act Cycles

PDSA cycles are a key methodology within the IHI Model for Improvement. This systematic approach encourages small-scale testing of prototype changes before full implementation. Through repeated PDSA cycles, teams can learn from each iteration, refine their approach, and progressively move towards achieving the aim.

Scaling up or scaling out: Start by testing your change on one person. If it doesn’t work, learn why and make changes to your plan. If it does work, then try it on 10 people. Learn from the results and adapt the plan accordingly. Next try it on a bigger scale or in a different area. Testing at a progressively bigger scale allows you to avoid expending large amounts of resources on a failed experiment and a large scale.

- Plan: Clearly define the problem or opportunity for improvement. Develop a plan that outlines the change to be tested, including what will be done, how it will be done, and the expected outcomes.

- Example: In an effort to reduce prolonged patient wait times, we will introduce a rapid triage system to prioritize patients based on acuity, and assign dedicated staff to assess and initiate care within 15 minutes.

- Do: Implement the planned change on a small scale. Collect data and observations during the implementation to understand how the change is affecting the process or outcomes.

- Example: Implement the rapid triage system and dedicated staff assignments in one section of the ED for a limited period. Collect data on patient wait times, staff workload, and patient satisfaction during this trial.

- Study: Analyze the data and observations to determine the impact of the change. Evaluate whether the change led to improvements, identify any unexpected results, and assess the feasibility of scaling up the change.

- Example: Analyze the data collected during the trial to assess the impact on patient wait times, staff efficiency, and patient satisfaction. Identify any challenges or unintended consequences.

- Act: Based on the findings from the study phase, make informed decisions about the next steps. If the change was successful, consider implementing it on a larger scale. If not, adjust the plan or try a different approach.

- Example: If the rapid triage system and dedicated staff assignments led to reduced wait times and improved patient satisfaction, implement these changes across the entire ED. If challenges were identified, modify the approach before scaling up.

What we learned from this first cycle can now inform a second PDSA cycle (either on a larger scale or with adjustments to avoid problems found in the first cycle). The cycle often occurs multiple times. This allows for continuous learning and refinement of improvement initiatives.

The project

Together we’ll identify a QI project and work through the steps. With your institutional credentials, you should be able to download this template. Download a copy, please don’t change the original.

This is the first draft of these instructions. If you have ideas on how to make it better, please let me know.

You must be logged in to post a comment.