Understanding “Human Error”

Humans make mistakes. Any system that depends on perfect performance by humans is doomed to fail. The risk of an accident is more a function of the complexity of the system than it is the people involved.

Humans are not the weak link in a process. We are a source of resilience. We have the ability to respond to unpredictable inputs and variability in the system. Systems should be designed acknowledging these facts.

The Quality Improvement process allows us to identify places where the system broke down and improve upon the design.

The contents of this post are based on the work of pilot and human factors engineer Sydney Dekker’s book “The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error.” Most of his work comes from analyzing industrials accidents and plane crashes. Most crashes are not solely the fault of the pilot but often multifactorial (non-standardized language, bad weather, overly crowded runway, equipment issues, etc). Under those conditions, any pilot could have made those mistakes. The system needs to be redesigned to set the pilot up for success.

Local Rationality

No one comes to work wanting to do a bad job. — Sydney Dekker

The local rationality principle asks us to understand why an individual’s action made sense at the time. “The point is not to see where people went wrong, but why what they did made sense [to them].” We need to understand the entire situation exactly as they did at the time, not through the benefit of retrospection.

In “M&M Conferences of Olde” the audience acted as Monday morning quarterbacks interpreting the findings of the case while already knowing the outcome. The provider at-the-time did not have the benefit of this knowledge. Of course they would make different decisions. Our goal is to understand the case the same way as the provider at-the-time did. Don’t be a Monday morning quarterback, instead put yourself in their frame-of-mind on Sunday afternoon.

Just Culture

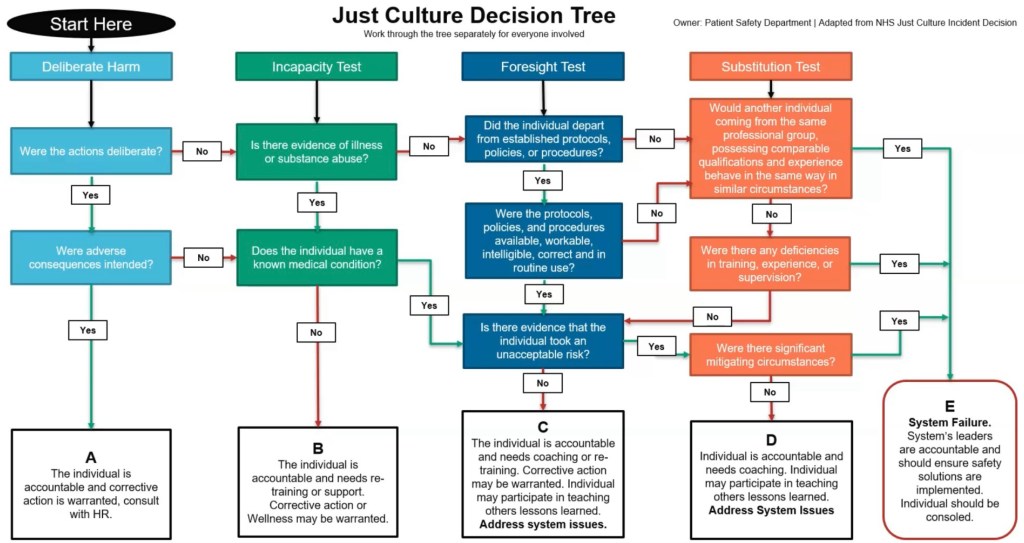

The Just Culture algorithm was developed by James Reason (Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents, 1997) and modified to apply to medicine. We ask a series of questions to determine the cause of an adverse event and offer an appropriate response.

- Deliberate Harm: Did the individual intend to cause harm? Did they come to work in someway impaired? This is sabotage and the person should be removed from patient care and dealt with appropriately.

- Incapacity Test: Was the individual impaired (eg, medical conditions, substances)? Remove the person from patient care, provide appropriate support and corrective actions as warranted.

- Foresight Test: Did the individual deviate from established policies, protocols or standard of care? If so, were the policies difficult to follow or did the person knowingly take reckless risks? If the former, explore systems issues. If the latter, reckless behavior may need to be addressed with corrective actions.

- Substitution Test: Could others with the same level of training have made the same choices? If so, this is a no-blame error.

An adverse event that passes all these tests reveals that system errors are likely at fault. Don’t blame the individual.

Analyzing Adverse Events

The single greatest impediment to error prevention in the medical industry is that we punish people for making mistakes. – Dr. Lucian Leape

We needed a new approach if we wanted to encourage bringing errors into the light for analysis to learn from these mistakes. Dekker describes six steps.

Step One: Assemble A Diverse Team

The team should include as many stakeholder perspectives as are pertinent. In medicine, we would include physicians, nurses, technicians, patients and others. This team needs to have expertise in patient care (subject matter expertise) and in quality review (procedural expertise).

The one group not included are those who were directly involved in the adverse event. Their perspective will be incorporated through interviews, but they do not participate in the analysis. They often lack the objectivity needed and may suffer secondary injury from reliving the incident.

Step Two: Build a Thin Timeline

When looking at plane crashes, systems engineers review the contents of the flight recorder (black box). From this they can create a timeline of events during the flight. In medicine, our “black box” is the electronic health record. Looking at the chart, we can understand what happened and when.

But in order to know why things happened, to gain local rationality, we need to go further.

Step Three: Collect Human Factors Data

To understand why things happened, we need to get into the minds of the people who were there. Interview the people directly involved in the adverse event to get their point of view. This is best done as close to the incident as possible as memory tends to degrade with time.

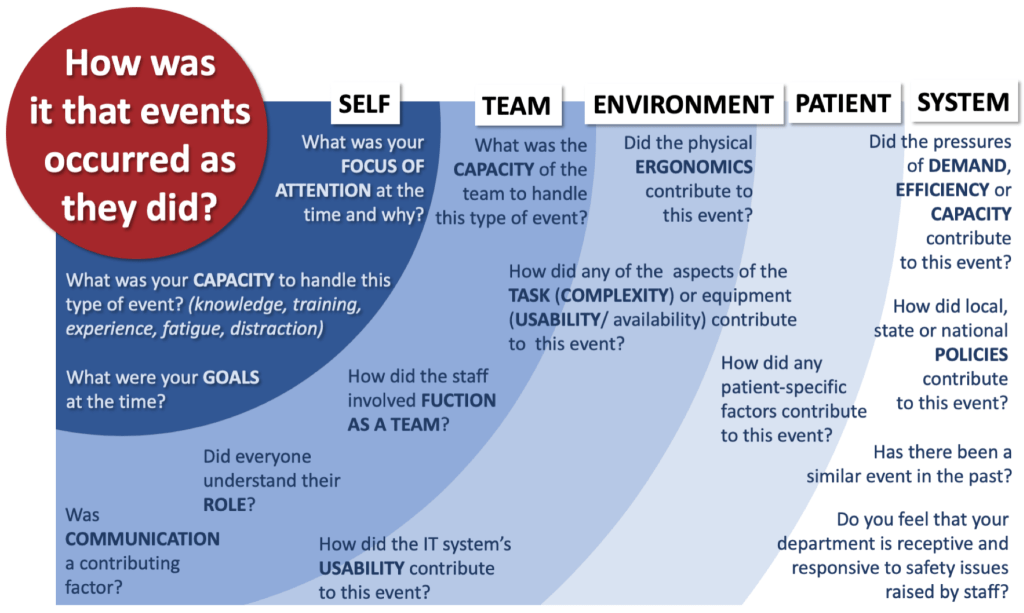

Understand what was happening in the room, why did they make the choices they did, and what was their understanding of the situation and why. George Duomos presented a series of questions on the EMCrit Podcast to guide the collection of this human factors data.

The following are good questions to ask during your debriefing with the staff that were present.

- SELF

- What was your focus of attention at the time and why?

- What was your capacity to handle this type of event, specifically knowledge, training, experience, fatigue, and distractions?

- What were your goals at the time?

- TEAM

- What was the capacity of the team to handle this type of event?

- how did the staff involved function as a team?

- Did everyone understand their role?

- Was communication a contributing factor.

- ENVIRONMENT

- Did physical ergonomics contribute to this event?

- How did the complexity of the task or usability of the equipment contribute to this event?

- How did IT usability contribute to this event?

- PATIENT

- How did any patient-specific factors contribute to this event?

- SYSTEM / CULTURE

- Did pressures of efficiency, capacity or flow contribute to this event?

- How did any policies (written or unwritten) contribute to this event?

- Has there been a similar event in the past?

- Do you feel that your department is receptive to safety issues brought up by staff?

Step Four: Build a Thick Timeline

With the human factors data in hand, overlay this on the thin timeline to build a thick timeline. This presents the events as they occurred within the context under which the providers were working. You may need to go back to interview providers repeatedly until you can understand what happened as they understood it at the time.

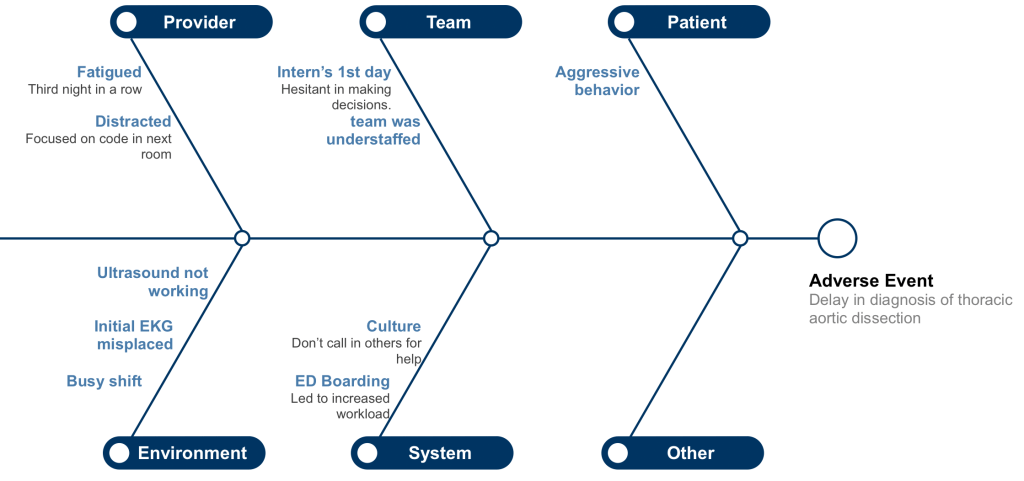

Step Five: Construct Causes

The causes of the errors are complex and often not readily available to be discovered. We need to work to understand and propose possible causes. One method of organizing the causes is in a Ishikawa diagram (or fishbone diagram). Here the spines of the fish are organized in the same categories as we looked at above.

This may require brainstorming by multiple people on the team. Come up with as many possible causes as you can.

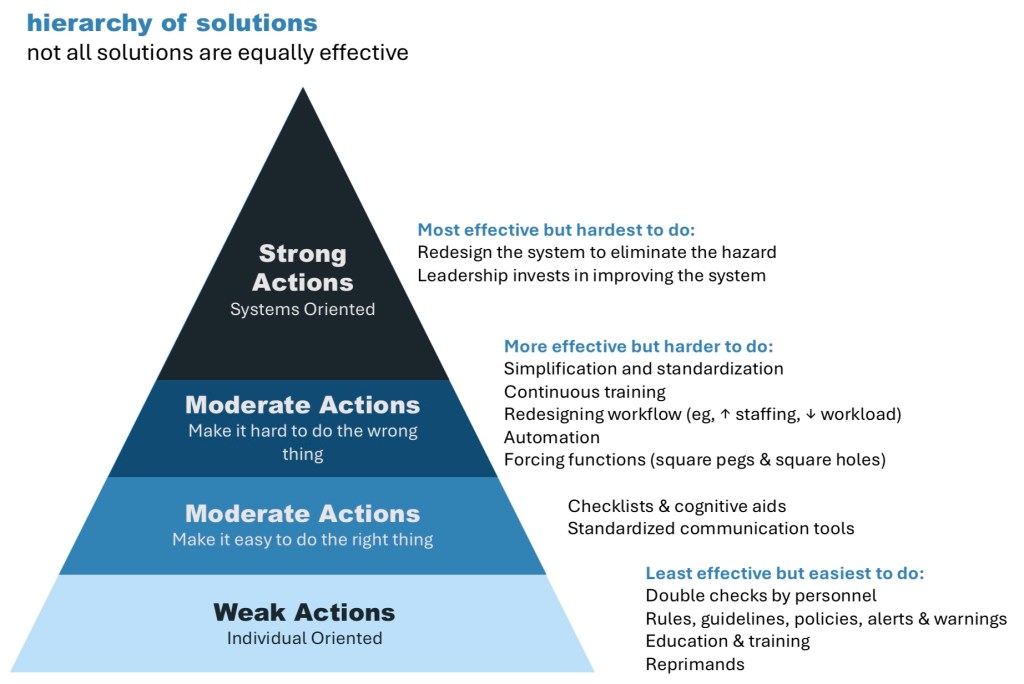

Step Six: Make Recommendations

At this point, we should have a good understanding of what happened. Now we need to propose potential solutions that would prevent this adverse event from occurring in the future.

Not all solutions are created equal. The ones that are easier to enact are often the least effective. The converse is unfortunately true, the most effective are the hardest to implement. Our goals, in order of effectiveness are to:

- How can we change the system to eliminate the hazard?

- How can we change the system to make it hard to do the wrong thing?

- How can we change the system to make it easy to do the right thing?

- How can we change individuals to make them do the right thing?

Pick one of the more important causes from your fishbone diagram and brainstorm different solutions to address it.

QI Slides

Use the case slides from the MM&I Instructions page to complete steps 1, 2, 3 and 4. Use the QI slides to walk through steps 5 and 6.

You must be logged in to post a comment.